Liquid smoke

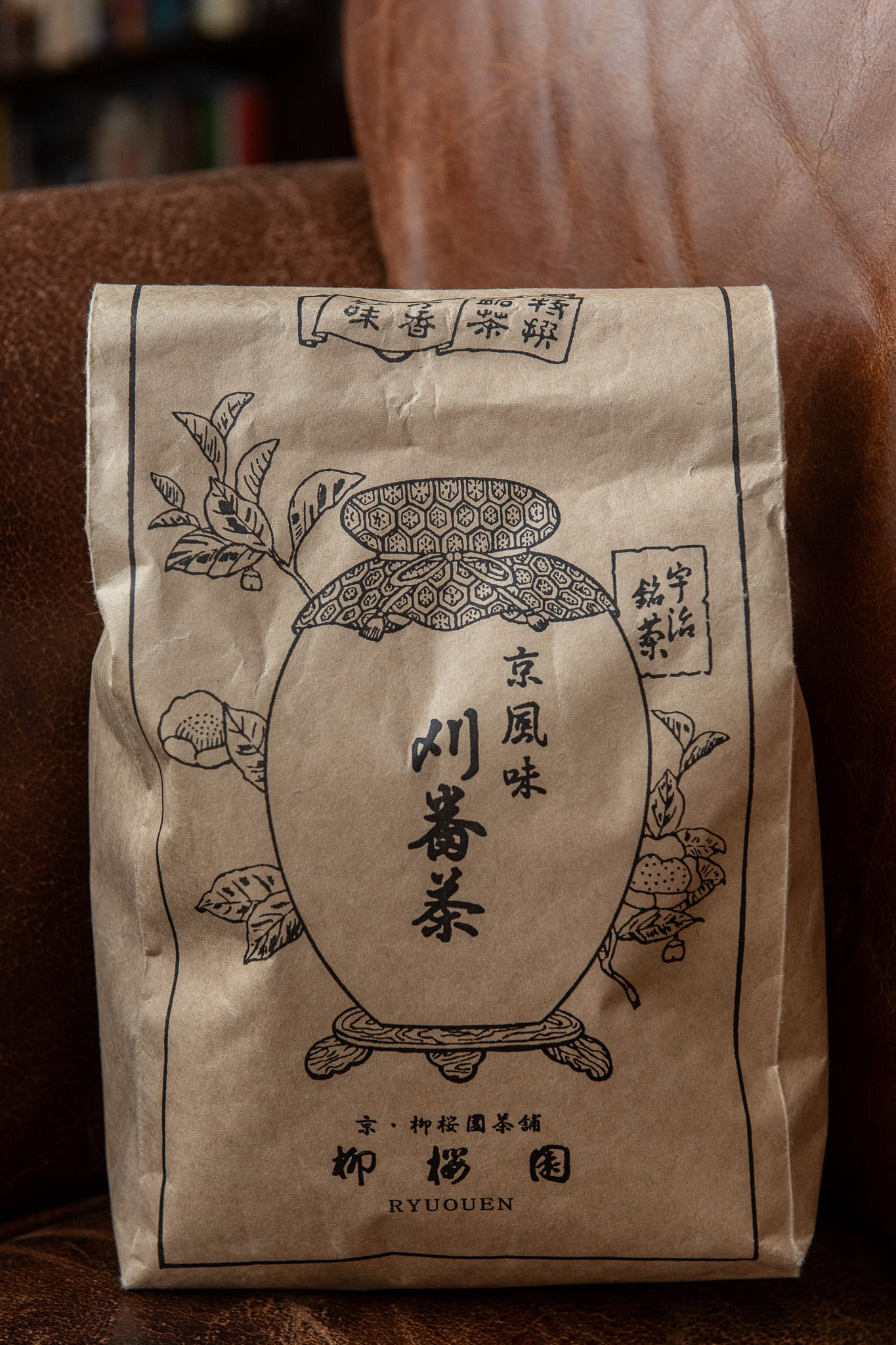

The tea: Iribancha roasted tea, sold by Kettl. $24 for 300g.

After new tender growth is plucked for spring and summer harvests, tea plants in Japan often need maintenance pruning. So towards the end of the growing season, farmers cut back long shoots of gnarly leaves to shape the plants back into neat waist-high bushes. The old discarded leaves from pruning are then used to make a rustic and utterly delightful tea called iribancha, or kyobancha.

Iribancha is both bracing and gentle. It’s like a smoke bomb when you first open the bag; the fragrance of cigarette butts, barbecue burnt ends, and pine sap fills the room. This aroma is only amplified during brewing. The first time I made some, I thought my living room would never recover from the smell. But in the cup, iribancha is light and mellow. The savory-sweet flavor reminds me of visits to maple sugar shacks during boiling season. Kyoto residents consider iribancha good for old people and their equally toothless grandchildren. It’s light in caffeine and shows no bitterness or astringency, even with prolonged brewing. You’ll know by the end of your first cup if you’re gonna get hooked on the stuff. If you do, you may be hooked for life.

The source: Paid subscribers have seen me hint at Kettl’s iribancha in the past. Tea seller Zach Mangan gets his from Ryuouen Chaho, a Kyoto tea shop and roaster that opened in 1875 and, among other honors, provides tea to the local Omotosenke tea ceremony school. Ryuouen sources their leaf from around the city of Uji and makes several kinds of hojicha (roasted green tea), of which iribancha is just one. Zach describes making iribancha as “more an art than a science.” While roasting in Chinese traditions is usually done over charcoal fires or in gas ovens, Ryuouen’s roasters incorporate direct thermal contact with superheated metal and ceramic, which brings an extra smoldering intensity to the leaf.

To brew: Iribancha is an everyday tea in Kyoto, and as such I think overly specific steeping instructions go against its casual spirit. You can drop a handful of leaves into a 2- or 3-quart pot of water on the stove and boil for a few minutes until the brew is to your liking. Or you can use a smaller handful in a regular teapot and steep for 3 to 5 minutes. The more I drink iribancha, the heavier my dosage gets. It’s an excellent tea for packing into a thermos. What’s non negotiable is the use of boiling water; this tea needs heat to fully express itself. Lastly, keep your bag tightly sealed after opening. These minimally processed leaves lose some of their magic if exposed to fresh air, even in just a few months. All the more reason to drink it often.

We have a few more open seats for our tea tasting session on Saturday, September 7th in Brooklyn! Get your tickets here.

Leafhopper is taking a break next week for Labor Day. See you back on the 10th, and until then, stay hydrated!

Sips in season

I’ve been waiting for the first whispers of autumn chill to write about iribancha. We’re just a few weeks from prime apple picking season here in New York, and as I plan a trip upstate, I feel a pregnant expectancy in the air. Autumn is coming, and the hints of its arrival usher my desire for deep roasted teas that seem made to meet the moment.

Of course in reality, they’re not. People in Kyoto drink iribancha throughout year. The same is true in Fujian, where roasted oolongs are served in all seasons. But I don’t live in a place with a single dominant tea tradition. I have the luxury to choose. And the longer I drink tea, the more it seems that my choice of teas happens in reverse. The teas choose me, often based on the changing seasons.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Leafhopper to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.